| That John Wilkes Booth was the assassin of President Lincoln, no one questions. However, was he the man who was shot and killed as the assassin on April 26, 1865 in a tobacco barn in Virginia? It's an interesting story, and one which piqued my curiosity when I discovered it while researching Lincoln's death. You see, there is a possibility that the real John Wilkes Booth escaped and lived under assumed names until he committed suicide in 1903. All accounts of Booth mention his curly black hair, yet two citizens who saw the body lying on the ground at the Garrett farm described it as red-haired. And Booth's personal physician, who examined the body the day after the shooting, recalled years later: “My surprise was so great that I at once said to General Barnes [the surgeon general], ‘There is no resemblance in that corpse to Booth, nor can I believe it to be that of him.’” |

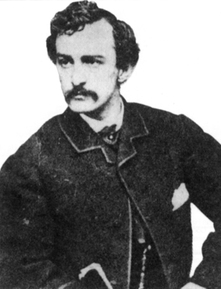

And there is an individual who confessed to being John Wilkes Booth in 1872. He went by the name of John St. Helen, and had befriended an attorney, Finis Langdon Bates, in Texas. St. John was the owner of a store. But he showed no interest in the business he bought, letting his assistant do all the work, and his ignorance of such trade essentials as liquor licenses led him to Bates. Bates found St. Helen, with his luxuriant black hair and moustache, “indescribably handsome” and noted that his poise, dress, and education set him apart from the more uncouth characters who inhabited the region. While others bellowed out bawdy drinking songs in the town tavern, St. Helen would recite Macbeth.

One day, thinking he was dying, St. Helen summoned Bates and gave him a photograph of himself with a curious instruction. If he died, Bates was to deliver the picture of St. Helen to Edwin Booth in Baltimore, and tell the famous actor how he had acquired it. St. Helen, however, survived his illness and in a lengthy and emotional confession that Bates transcribed, St. Helen — or Booth — described in detail the murder of Lincoln and his own getaway.

Bates was convinced his client had confessed the truth. Apparently deciding that this was a secret that should not be kept, he wrote to the army and urged them to reopen the case. To his dismay he received only a terse reply: The killer of Abraham Lincoln had been captured and shot by the U.S. Army and the case was closed.

In the meantime, the mysterious storekeeper named John St. Helen left town one day — and never returned.

Then, in 1903, a seemingly insignificant tragedy happened in Oklahoma: An itinerant house painter calling himself David E. George committed suicide in the small town of Enid. George was an odd, friendless old man, without the slightest talent for painting houses. In fact, he botched the one painting job he got during his brief stay in Enid. He much preferred to sit in the lobby of his boarding house and read old copies of theatrical journals. When he was drunk, which was often, he would quote Shakespeare and once lamented to his landlady, “I’m not an ordinary painter. You don’t know who I am. I killed the best man that ever lived.”

One night, George went up to his dreary room and swallowed a fatal dose of poison. Such a death would have rated only a few lines on the obituary page of the Enid paper, but for one element. On his deathbed, George told the minister that he was John Wilkes Booth.The minister passed that information on to the local undertaker, who took special pains to preserve the body.

Newspapers had carried the strange tale of David George as far as Memphis, and Bates hoped this was the missing link he had long needed. When he finally arrived in Enid, he was ushered into the rear of a furniture store where the body was kept. He lifted the cloth from the dead man’s face and cried out, “My old friend! My old friend John St. Helen!”

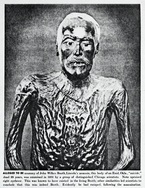

No one claimed the body, and in 1904, Finis Bates took the mummy to Memphis, where he carefully stored it in a coffin-like box in his home. Bates felt compelled to tell the truth of the matter, and wrote a 300 page book professing that the mummy was the real John Wilkes Booth. It made good reading, but the “Washington officials” never came for the assassin’s body, and the mummy lingered in Bates’ garage.

Experts who examined the mummy found a shriveled old man with long white hair and dried skin like parchment paper. They noted a similarity between this creature and John Wilkes Booth, and scars that Booth carried matched vague marks on the mummy. The left leg was shorter, as if it had once been broken, and the mummy’s right thumb was deformed (Booth had crushed his thumb in a stage curtain gear earlier in his career). The size of the mummy’s foot matched a boot left behind by Booth during his flight. And Chicago doctors who X-rayed the body in 1931 discovered a corroded signet ring in the mummy’s stomach — with the initial “B.”

Twenty years later, Bates’ widow sold it to a carnival for $1,000. Over the next few years it changed hands several times, always bringing bad luck to its owners, so the story goes. At one point, the mummy was displayed on an Idaho farm under the homemade banner, “See the Man Who Murdered Lincoln.”

Attempts were made to have the body of the deceased assassin in Baltimore exhumed so scientists could confirm its identity (by matching its DNA with surviving family members). After all, if Booth escaped, then who is buried in the family plot in Baltimore? The Booth family never agreed to the exhumation.

And so, the mystery remains unsolved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed