| A unique WW2 love story! Now Available for Pre-Order on Kindle A PASSING MIST BOOK 3, RIDGELY RAILS LEGACY When the U.S. enters WW2, Gloria joins the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps in hopes of adventure. Her escape is short-lived, however, and duty calls her back to the family farm—but returning to Ridgely means facing memories she’d rather leave behind. As she struggles to make peace with her past, a new challenge arises. German POWs are hired to help work the farm... Gloria never imagined she would find love again, and certainly not with a man on the wrong side of the war. Having already thrown off feminine stereotypes, Gloria is used to facing criticism. But a romantic relationship with a “Nazi soldier”—regardless of his true affiliation—is more than unacceptable, it’s dangerous. In a world torn by war and hate, how can they hope to build a future together? |

|

0 Comments

This is the story of the real-life Franz who inspired the character by the same name in my novel, A PASSING MIST. It is the account shared by Annice Ebling Fike in the Caroline Sun Historical Booklets, Vol. 8, p. 268. It was the late years of World War II that our apple orchard near Cordova was having a big problem to secure workers to pick apples. It was my husband (Norman Fike) that read an ad in the local newspaper about German prisoners being available to help with farm work. The next day Norman contacted the man in charge of the prisoners for the rules and requirements, which he readily agreed to.

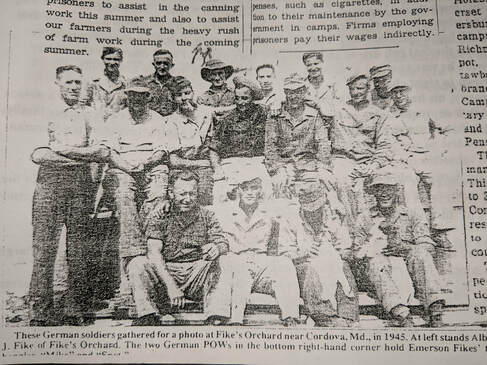

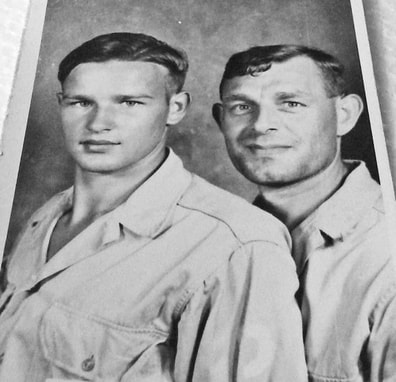

On Monday morning, early, my husband drove our farm truck to the old Easton airport to collect the prisoners. He was allowed 20 POWs. Each prisoner brought a small brown bag with them for lunch, the camp sent a couple of men as guards. We soon discovered none of the prisoners had ever picked apples. It was the first apple orchard they had ever seen. Only a few of the POWs could speak good English, most of the group were very young boys, the older men had been lawyers or business men in Germany. The prisoners seemed willing to work, they were smart and learned quickly. After a couple of days the guards no longer came with the prisoners, we were satisfied with their working ability, but my husband did not think the prisoners were receiving enough food. Their brown bag held two pieces of bread and a thin slice of lunch meat. The prison camp rules were you could not feed the POWs. The Fike family had a discussion on this rule and decided for both parties involved, they would supply a little extra food at lunch time. Each day a large pot was on the stove with soup, stews, or any local cooked vegetables, along with a milk can of ice tea. For a dessert, the group seemed to like best a square of gingerbread. The extra food made the workers happy. They easily handled all kinds of chores at our apple orchard and we were able to supply the local area with apples. One of the youngest prisoners became a friend with my husband's brother, who was 18. The prisoner was 16 years old, his name was Franz Krautcreamer. He was intelligent and learned to speak English quickly. The first time he came in our house, tears came in his eyes when he saw our piano. His family had a piano before the war. We asked Franz to sit down and play our piano, within minutes we knew he was good at playing the piano. In November of 1945 the German prisoners were pulled out of this country and returned to their homeland. Our family was sorry to see them leave because they had become more than just workers. They had become our family friends, most had picked up enough English to make good conversation. In the months after the POWs had left this country, we continued to receive mail from many of the group who had worked at our orchard. The oldest person in the group was in his forties, wrote to tell of his marriage. The net year when he wrote, his wife had a baby boy and he named him "Norman" because of the kindness our family in war time had shown him. My greatest surprise of the prisoners came many years later, as we had kept in contact with our 16 year old Franz. He had went to college, then married and had a large family and became a wealthy business man, due to a navigation invention he had made. It was an afternoon in 1970 when a Washington taxi stopped at our back door and a man carrying an armful of flowers knocked on our back door. I opened the door and recognized Franz Krautcreamer. We hugged and both did cry. He had planned this stop because we were the American friends who had smiled and showed kindness to a scared 16 year old boy imprisoned in a foreign country in war time, this he never forgot. We all had dinner, including the taxi cab driver, and talked for hours. Franz then had to leave to catch the plane to Florida, where he was opening a business office. He made us promise to visit him in Germany. His family had grown to eight children. We did visit Franz in Germany. His home was a 16-room restored castle on the Rhine River! We got a deluxe tour of Germany and it was a such an enjoyable trip, we later made a second trip to visit the Krautcreamer family. All because of giving a helping hand to a stranger in war time, our family made good friends with a German family twenty years later. --Annice Ebling Fike This the story of Herbert Stoerzer, a German POW during World War 2, as shared by his son Karl in the Dorchester Banner. Submitted to Dorchester Banner/Karl Stoerzer Herbert Richard Stoerzer, at left, was one of the many German prisoners who worked at the Phillips Packing Plant in Cambridge during the Second World War. He was captured after being wounded in Normandy in June, 1944. CAMBRIDGE — “I wonder if you would be interested,” Karl Stoerzer said in a phone message to Dorchester Banner. Mr. Stoerzer was referring to his father’s time as a German prisoner of war in Cambridge, working at the Phillips Packing Company. He said he had information, photos and even his father’s diary, with references to the young soldier’s time in Easton, Cambridge and other areas in 1944 and 1945. The answer to Mr. Stoerzer’s question, of course, was yes. Captured in Normandy Herbert Richard Stoerzer was drafted into the Wehrmacht, or regular German Army, in early 1944, just in time for basic training and a trip to the front lines. The Allies had invaded France with the Normandy Landings on June 6, and he found himself fighting there soon afterwards. In his diary, brief entries made after his capture recorded the events. 24 Juni wurde ich verwundet – “June 24 I was wounded.” The diary continues, 6 Tage im Feldlazeret in Frankreich anschliessend kurze zeit in England – “Six days in a field hospital in France, then a short time in England.” He crossed the Atlantic in a ship he remembered as the “Alexander,” landing in New York on July 27, 1944. The next day, he arrived in a camp in Easton, where he stayed until Nov. 9, when he was transferred to Cambridge. Memories of Maryland His son Karl lives in Lexington, Ky. As he was returning there from a vacation, and ready to pass through the Eastern Shore, he realized he could share details of his father’s history. “He liked it in Maryland,” Mr. Stoerzer wrote later in an email to The Banner, “And always said that local farmers with German ancestry treated them well, and promised them jobs after the war was over.” Under the terms of the Geneva Convention, it was prohibited to put prisoners to work on weapons or ammunition. Many captured Germans, therefore, worked in food production. Phillips Packing Company’s Plant F was already the nation’s largest fruit cannery before the war. When the United States entered the war, production at the plant shifted to C rations, pre-cooked meals packed for the military. Though it has been years since the plant produced canned goods, the building is still there, on Dorchester Avenue. It houses businesses now, and is undergoing a revitalization. Decent treatment and pretty girls While he was in the States, Herbert Stoerzer found that not everything was tough. On their way to work in the back of trucks, they would wave at pretty girls, his son said. The decent treatment — and maybe the girls — helped create a good impression for the soldier, who returned to settle in the United States in 1954. But there were still some challenges to face before he could do that. When the war ended in 1945, that didn’t mean that everyone went home right away. For one thing, Germany was in ruins and there wasn’t enough housing for the people already there, never mind returning troops. And as for the prisoners, Allied leaders were not enthusiastic about allowing millions of captured soldiers to return all at once. Not that the elder Mr. Stoerzer was involved in politics, though. He was, “a young, innocent, naïve kid getting drafted into the Wehrmacht, along with many other poor young men, all through no fault of their own,” Karl Stoerzer wrote. “His brother was in Russia, the whole time, and my grandfather was in Russia in both WWI and WWII. Both were very lucky and survived.” He continued, “I do remember a story he told about some of the longer-term POWs in Cambridge who were more ideologists than the younger newly arrived. This group, to the dismay of the new arrivals, still believed that Germany would win the war, and would try to paint a swastika on the water tower. Of course, the new POWs disavowed themselves from this group.” A soldier’s journey ends But politics or not, there were reparations to be made. When the men crossed the Atlantic again, in 1946, they thought they might be returning to Germany. But instead, they were brought to Belgium, where they “almost starved to death,” Karl Stoerzer said. After a year there, so close to home, it was the turn of the British, who also wanted the prisoners’ labor. It wasn’t until another year and a half had gone by that the men were allowed to return to Germany. 27 Nov. 1947 Nun endlich wird die Fahrt nach der geliebten Heimat wahr – “Now, finally, the journey to the beloved homeland comes true.” “Despite being a POW, he was grateful for his good treatment in Maryland, and it definitely sparked his interest in America, and contributed to his decision to move here with his family, in 1954,” Karl Stoerzer said. “He saw it as a land of opportunity, worked hard, was very successful as a textile tool maker and lived the American Dream.” https://www.dorchesterbanner.com/local-history/stoerzer-father-was-pow-in-cambridge/

|

Rebekah Colburn Novelist Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed