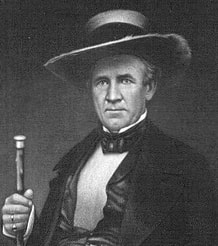

If you know anything about history, especially Texas history, you’ve at least heard of Sam Houston. When I began researching for this novel, I didn’t know a whole lot about him. The more I studied his life, the more I discovered what an interesting and complex person he was.

He was relevant to DRIVEN BY THE PRAIRIE WIND because he was the first president of the Republic of Texas, in office at the time that Risdon and Lucy Bloodsworth learn they can have “free land” if they can simply cross the country to stake their claim, live for five years on the property, and make improvements to it.

I didn’t take a particular interest in Sam Houston until I discovered that he also had connections to my Cherokee characters, Caleb and Jane Lowe. As I researched back and forth between the details for both storylines, I kept encountering the same man: Sam Houston. I never expected him to be the common thread that weaves back and forth between these two different worlds, but his name kept popping up in Texas and in the Cherokee Nation.

Since I found his life story to be noteworthy, I thought I would share some of the highlights, including: his adoption by the Cherokees; the odd circumstances of his resignation as governor of Tennessee after a very brief, failed marriage; and his propensity for violence and drunkenness oddly mixed with moral courage—which may have led to his military and political success. I mean, he beat the Mexican Army in eighteen minutes! All in all, he’s a fascinating character.

| Sam Houston was born in Virginia in 1793, but his mother relocated him and his eight siblings to Tennessee after his father’s death. Both his parents were descended from Scottish and Irish immigrants who had settled in Colonial America in the 1730s. In Tennessee, his mother built a cabin, cleared a farm, and opened a store. Sam was expected to help with these responsibilities, but he preferred reading the Greek classics from his father’s library or exploring the Tennessee frontier. (Who can blame him?) It was on such excursions that he met the Cherokee, (the farm bordered the Cherokee Nation) and when he disappeared at the age of sixteen, his brothers located him on Hiwassee Island, located at the confluence of the Tennessee and Hiwassee Rivers. He had taken up residence with the Chief, John Jolly, and informed his siblings that he preferred to remain with the Cherokee. According to Indian Agent Return J. Meigs, Jolly owned "one of the largest ... finest homes in the South." |

| Chief Jolly gladly welcomed Sam Houston into his home, adopting him as a son and bestowing upon him the Cherokee name Colonneh, meaning "the Raven." Despite his status, Jolly dressed in buckskin hunting shirts, leggings, and moccasins. Houston followed suit, learned the Cherokee language, dances, ball games, and how to hunt wild game. For three years, Sam Houston lived among the Cherokee. Although he reentered the world of white men, his life would be forever changed by this experience, and he would return to his adopted father in his hour of greatest need. At the age of nineteen, Sam already had a reputation for drinking too much. Since he had run up debt in Haiwassee, Houston briefly took a job clerking at a store in Kingston before returning to Maryville to open a one-room schoolhouse. Perhaps it wasn’t exciting enough, and a year later, he enlisted in the United States Army and was immediately appointed a sergeant. He fought under Andrew Jackson at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814, alongside several Cherokees whose names also appear in my novel: John and Lewis Ross, Major Ridge, and Junaluska. |

The following year, 1818, Houston received a strong reprimand from Secretary of War John C. Calhoun (whose name is associated with secession and who resigned from his role as Vice President under Jackson to represent South Carolina as a senator). Sam Houston arrived in Native American dress to a meeting with the Cherokee leaders and Calhoun. His intention was to demonstrate respect to the Cherokee, but Secretary of War Calhoun was not impressed. He felt it was unbecoming behavior for an officer and held the faux pas against Houston for the rest of his life.

| Sam’s next adventure was to move to Nashville, TN, and apprentice under a judge. He was soon admitted to the state bar and opened his own legal practice in Lebanon. He went on to become district attorney for Nashville, while also being appointed as a major general of the Tennessee militia. In 1823, he won a seat in the House of Representatives, and in 1827 he was elected as the governor of Tennessee. He was aided in his political career by his mentor, Andrew Jackson (no one’s perfect). Everything was on track for a successful political career. Then, in January of 1829, he married the daughter of a wealthy plantation owner. Eliza Allen was only nineteen years old; he was thirty-five. Eleven weeks later, he resigned from the governorship. So, what happened? Wouldn’t we all like to know! Some say that she married him only to please her father and was in love with another man. Others believe she was repulsed when his wound from the Battle at Horseshoe Bend was exposed, that it was a festering sore involving his intestines which gave off an offensive odor. It is said they spent their wedding night apart. (If this is true, can you blame her?) |

Houston seemed clueless as to what had happened in his relationship (typical man?). He wrote to his new father-in-law in April, expressing his confusion over his wife’s seeming indifference toward him and asked for advice on how to restore their relationship. Two days later, when Houston traveled to Cockrill Springs for an election debate, Eliza returned to her family on horseback.

When Houston was asked to make an official statement about the separation, he said "I can make no explanation. I exonerate this lady fully, and do not justify myself."

On the 15th of April, he went to Eliza and knelt on his knees before her, begging with “dramatic force” to take him back and return to Nashville with him. She was unmoved.

The following day Sam Houston resigned as governor of Tennessee.

According to reports, on April 23 he wore a disguise and boarded a steamboat out of Nashville. He went to Arkansas Territory and returned to the place where he was most comfortable: with the Cherokee Nation and his adoptive father, John Jolly. En route, however, Houston was intercepted by Eliza’s brothers who explained that there were a number of rumors surrounding his separation from their sister.

Houston told the brothers to "go back and publish in the Nashville papers that if any wretch ever dares to utter a word against the purity of Mrs. Houston I will come back and write the libel in his heart's blood."

Such an interesting break-up!

Although prior to this heartbreak, he may have had a drinking problem, now he earned a new name among the Cherokee people: "Big Drunk." He also lost the approval of Andrew Jackson, who had helped him become a congressman and the governor of Tennessee. (No big loss.)

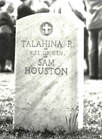

| In the summer of 1830, Sam Houston took a second wife. She was a Cherokee woman and they were wed in a native ceremony. Her name was Tiana, sometimes called Diana Rogers; she was the daughter of Chief John "Hellfire" Rogers. Her grave is marked Talahina Rogers. It was a second marriage for both of them. She was widowed from her first marriage, with two children. They settled near Fort Gibson and managed a trading post. During this time, because of his political experience and his connection with President Jackson, Houston was asked to go to Washington to mediate disputes for the Native American Indians. |

There was an Ohio Congressman named William Stanbery who was not a fan of Jackson (can’t blame him), and who accused Houston of colluding with the government to defraud the Cherokee while he was Governor of Tennessee. As you can imagine, Sam didn’t respond too well to this accusation. He wanted either an apology or a duel. Stanbery refused to give him either.

On April 13, 1832, Sam Houston and two members of the U.S. Senate were walking along Pennsylvania Avenue on their way to the theater. Unfortunately for Stanbery, he chose this exact time to leave Mrs. Queen's boarding house and go for a walk.

Mr. Stanbery has been described as “a vile toad of a man” with “black ink drops for eyes that sat too close together on his melon-like head. Long creases on his face emphasized his thin, broad, perpetually downturned mouth.” I’m sure after reading that, you’re as curious as I was to what this man really looked like. So, here he is…

| A rather recognizable silhouette even on a lamplit street, Houston immediately saw the rotund figure and approached him with blazing eyes. Carrying a hickory cane, Houston wasted no time in planting it atop the large man’s head. It was not his finest moment, to be sure. While shouting, “You damned rascal!” Houston liberally applied his cane to the congressman. Stanbery, understandably shaken, drew his gun and fired directly at Sam’s chest. It wasn’t Houston’s time to meet his maker, apparently, as the gun misfired. Houston continued to strike his enemy with infuriated gusto. The incident ended when Houston felt he had sufficiently expressed his feelings and continued to the theater, leaving Mr. Stanbery to stagger back to the boarding house to nurse his wounds. |

| Needless to say, that sort of behavior is generally frowned upon on Capitol Hill. Congress ordered that Houston be arrested and tried. He lawyered up with a fellow whose name should be familiar to all Americans: Francis Scott Key. Between the advocacy of his attorney and the help of friends like James K. Polk, Sam Houston was essentially slapped on the wrist. He was given a verbal reprimand and ordered to pay $500 in damages. Obviously, although there were no serious consequences for his loss of temper, the incident badly damaged his reputation. Luckily, there was a place he could go to start over and reinvent himself: TEXAS. His Cherokee wife, Tiana, (Diana or Talahina or whatever her name was), opted to remain in Indian Territory when he departed in December of 1832. The marriage was peacefully absolved; she retained the titles to their residence and land. |

He settled in the town of Nacogdoches, Texas and opened a law practice. He also pursued a divorce from his first wife, Eliza Allen, (apparently, they had been legally married throughout his relationship with Tiana). The divorce was granted in 1837 and Eliza remarried in 1840. Houston reentered politics, serving as a delegate for Nacogdoches in 1833, proposing to the Mexican Congress that Texas be separated from Coahuila and granted statehood. No such agreement was made, and in 1834, Antonio López de Santa Anna assumed the presidency.

| Houston was in the right place at the right time, so to speak, for a man with military background and repressed anger issues. By October of 1835, Houston agreed with those who believed Texas needed to be separated from Mexico and became commander in chief of troops to begin the “work of liberty” in Nacogdoches. In February 1836, Houston helped to negotiate a peace treaty with the Cherokee Indians in East Texas, and in March, he served as a delegate to a convention where the assembly adopted the Texas Declaration of Independence. Almost immediately, Houston received the appointment of major general of the army from the convention and began to organize the republic's military forces. His volunteer force of rebels were not disciplined soldiers, and the Mexican Army was empowered after their recent defeat of the Americans at the Alamo. Houston needed time to train his men and acquire equipment and provisions before they would be ready to face Santa Anna. |

During that time, he negotiated for his old friends, the Cherokee, to peacefully live within the borders of the Republic of Texas. His successor, Mirabeau Larimore, had very different ideas about the Native Americans.

| In 1840, the same year that his first ex-wife remarried, Sam Houston tied the knot for the third time. And, as unlikely as it may seem, the third time was the charm for him even though his new bride was only twenty-one years old (he was 47) and she was a devout Baptist. She must have been one brave woman! They remained married until his death, having eight children together. She influenced him to curb his drinking habits, which had plagued him throughout his life, but the most remarkable achievement was in 1854, when he chose Believer’s Baptism. After fourteen years of praying for her husband and trying to convert him, Margaret Moffette Lea watched as the old cuss was immersed in the waters of Little Rocky Creek. |

When Texas joined the union in 1845, Houston became one of its two United States senators. He ran for governor in 1857 but was defeated. He ran again in 1859 and was elected Governor of Texas.

Although he was a slaveowner, Houston had always voted against the spread of slavery into new territories. He furthermore was a Unionist and opposed to any ideas of sectionalism or secession. Because of this unique Southern position, the National Union party convention in Baltimore almost nominated him as a Presidential candidate in 1860, but he narrowly lost to John Bell.

| As you know, Abraham Lincoln was elected, and the nation split down the middle. Houston tried to advocate for peace within Texas, but they would have no part of it. He was booted out of office and even though Lincoln offered Houston the use of federal troops to keep him in office and Texas in the Union, he declined. Out of love for Texas and not wanting to be a source of bloodshed, Houston quietly took his wife and children and moved to Huntsville. In 1863, at the age of seventy, Sam Houston died of pneumonia. But his name will forever be synonymous with Texas. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed