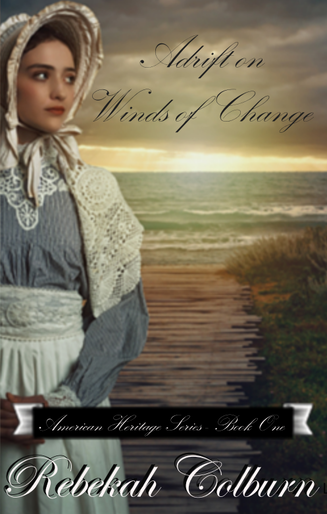

| An historical drama set on the lower Eastern Shore of Maryland, ADRIFT ON WINDS OF CHANGE brings a unique perspective to the Revolutionary War in the Chesapeake Bay. I had hoped to have it in print by now, but you now how plans change! I am still working on polishing it with final edits from my husband's fourth reading of the manuscript, and have taken his suggestion that my previous cover idea did not accurately reflect the content of the novel. He said it's more exciting and has a much broader appeal than what the cover suggested. So, here I present to you the remade cover of ADFRIFT ON WINDS OF CHANGE! |

|

0 Comments

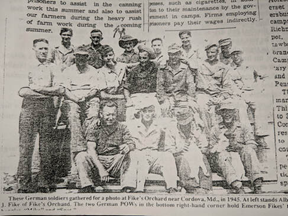

When the U.S. enters WW2, Gloria joins the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps in hopes of adventure. Her escape is short-lived, however, and duty calls her back to the family farm—but returning to Ridgely means facing memories she’d rather leave behind. As she struggles to make peace with her past, a new challenge arises. German POWs are hired to help work the farm... Gloria never imagined she would find love again, and certainly not with a man on the wrong side of the war. Having already thrown off feminine stereotypes, Gloria is used to facing criticism. But a romantic relationship with a “Nazi soldier”—regardless of his true affiliation—is more than unacceptable, it’s dangerous. In a world torn by war and hate, how can they hope to build a future together? Combining history and fiction is always fun, but writing this novel was particularly enjoyable for me! There were a lot more historical details to work with on a local level, thanks to the newspaper articles and interviews with senior Ridgely residents recorded in Rampmeyer’s historical booklets. I also tied in some elements of personal interest to me, such as a woman’s role in society and the identification of verbal and emotional abuse as domestic violence. This time period is often studied for a variety of reasons, one of which is our fascination with the arch-villain, Adolph Hitler. And a forbidden romance always adds a little bit of excitement. When I learned that there had been German Prisoner of War Camps on the Eastern Shore, and in Caroline County, I knew I had the basis for a great story! As our hometown boys either enlisted or were drafted, it created a shortage of hands to work the local farms and canneries. The Department of Agriculture decided that the German POWs were the solution to this problem. Rather than merely taking up space waiting for the war to end and placing additional needs on the government to provide for them, the POW’s could make themselves useful and earn wages to pay for their keep. They were bussed out daily to farms and canneries throughout the area, many of the prisoners developing friendships with the locals they came to know.

Each prisoner brought a small brown bag with them for lunch, the camp sent a couple of men as guards. We soon discovered none of the prisoners had ever picked apples. It was the first apple orchard they had ever seen. Only a few of the POWs could speak good English, most of the group were very young boys, the older men had been lawyers or business men in Germany. The prisoners seemed willing to work, they were smart and learned quickly.

One of the youngest prisoners became a friend with my husband's brother, who was 18. The prisoner was 16 years old, his name was Franz Krautcreamer. He was intelligent and learned to speak English quickly. The first time he came in our house, tears came in his eyes when he saw our piano. His family had a piano before the war. We asked Franz to sit down and play our piano, within minutes we knew he was good at playing the piano. In November of 1945 the German prisoners were pulled out of this country and returned to their homeland. Our family was sorry to see them leave because they had become more than just workers. They had become our family friends, most had picked up enough English to make good conversation. In the months after the POWs had left this country, we continued to receive mail from many of the group who had worked at our orchard. The oldest person in the group was in his forties, wrote to tell of his marriage. The next year when he wrote, his wife had a baby boy and he named him "Norman" because of the kindness our family in war time had shown him. My greatest surprise of the prisoners came many years later, as we had kept in contact with our 16 year old Franz. He had went to college, then married and had a large family and became a wealthy business man, due to a navigation invention he had made. It was an afternoon in 1970 when a Washington taxi stopped at our back door and a man carrying an armful of flowers knocked on our back door. I opened the door and recognized Franz Krautcreamer. We hugged and both did cry. He had planned this stop because we were the American friends who had smiled and showed kindness to a scared 16 year old boy imprisoned in a foreign country in war time, this he never forgot.b v We all had dinner, including the taxi cab driver, and talked for hours. Franz then had to leave to catch the plane to Florida, where he was opening a business office. He made us promise to visit him in Germany. His family had grown to eight children. We did visit Franz in Germany. His home was a 16-room restored castle on the Rhine River! We got a deluxe tour of Germany and it was a such an enjoyable trip, we later made a second trip to visit the Krautcreamer family. All because of giving a helping hand to a stranger in war time, our family made good friends with a German family twenty years later.” My own Franz is a composite character inspired by these two stories. As Gloria comes to terms with her failed marriage with a local who still works at the Breyer’s Condensing Plant where she must help her father deliver milk from their dairy cows, you glimpse a picture of Ridgely in the 1940s. There was even an observation post where men, and eventually women too, took turns watching the skies and documenting every aircraft that flew over. They practiced blackouts, darkening all the windows whenever the siren was heard. Gloria’s mother, Sophie, had endured the Great War and her life had been dramatically shaped by its events. Now, Gloria must face the challenges of her own day, far more complex as the “enemy” shooting at her brother overseas is also working shoulder to shoulder with her on the family farm. Often remembering the words of her grandmother, Ella Mae, Gloria chooses to forge a path true to her own independent spirit. She even takes a job at the Feed Store, owned by Martin Sutton (after whom the Ridgely Park is named), hoisting heavy sacks of grain over her shoulder in her denim overalls. Gloria knows that Franz is more than just a good looking, exciting diversion, and she believes their love is worth taking whatever risks are required. Although the Ridgely Rails Legacy ends with this novel, the story of Gloria’s family continues in the next series with her niece, Natalie, in the Time Returns Series, set in the town of Greensboro, Maryland. For more information on how to purchase my novels, or to learn more about my other series, you can go to my website, RebekahColburn.com. You can also view my blog articles between April and July of 2019 for more details about the Ridgely Observation Tower, Breyer’s Condensing Plant, and German Prisoners of War on the Eastern Shore. If you would like to read my article, A BIBLICAL PERSPECTIVE ON ABUSE, MARRIAGE, AND DIVORCE, it is found in my blog archives, dated 6/25/2019.

“Although she was only fifteen that day, Sophie understood that the significance of the fountain was not just to slake the thirst of the farmers as they went to sell their produce at the railroad station with their team of mules or horses, or to give relief to dogs wandering through the town’s dusty streets on a hot summer’s day. No, the value of the fountain lay in its purpose to demonstrate love and mercy.

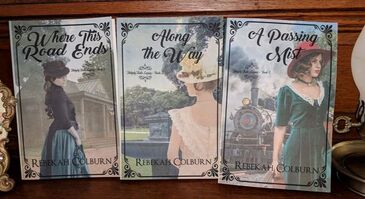

Such platitudes would not have meant so much if across the ocean there wasn’t a horrible war waging which had taken the lives of thousands upon thousands of men and would take the lives of many more before it ended. In the face of unspeakable hatred and brutality this fountain was a monument to celebrate kindness, and a statement of hope that one day peace would reign again.” I don’t want to give the plot away, but the war would change the course of Sophie’s life as it did for so many others. Her new path includes joining Alice Paul in the fight for suffrage and participating in the Watchfire Demonstrations in D.C., which results in her being jailed and learning firsthand that freedom and democracy are noble words, but not always lived out in the same way they are preached. A romance story which captures the struggles of the era and the impact it had on the families of the Eastern Shore, ALONG THE WAY also demonstrates that kindness, courage, and determination can make the world a better place. Following is the back cover synopsis: It may be forever we part, little girl, And it may be for only a while. But if fight, Dear, we must, Then in God is our trust. So, send me away with a smile. -- John McCormack, 1917 Sophie is seventeen when the United States joins the Great War and the mandatory conscription is enacted. All her dreams hang in the balance when her fiancé is drafted and sent to France to fight in the trenches. Searching for comfort and purpose, Sophie turns to her love of music, and through it, finds more than she ever expected. As she discovers new strength, Sophie feels compelled to take on a greater cause. While the young men are battling overseas in the name of democracy, she joins the crusade at home for women to have a voice in their government. Persevering through her own personal fears and losses, Sophie clings to the hope that the world—and her life—will one day be at peace again.  This month, I want to highlight the first book in the RIDGLEY RAILS LEGACY series. Last month I included a short synopsis of the story, but in this article, I’d like to provide the back cover summary as well as some inside information on the novel and its cover. “Suffering has been stronger than all other teaching... I have been bent and broken, but--I hope--into a better shape.” – Charles Dickens, Great Expectations Ella Mae Hutchins knows exactly what she wants from life. Getting it turns out to be much harder than she expects. She has only two dreams: to marry Daniel Evans and to become a successful novelist. When neither dream seems achievable, she sets out to build a life without either. After all her efforts fail, Ella Mae returns to her hometown broken. Determined to start again, the last thing she expects is to encounter the man she blames for ruining her life. Although age and suffering have changed them both, can she forgive Daniel for breaking her heart and is she brave enough to hope for a writing career in a time when female novelists are rare? It doesn’t take much imagination to know where the inspiration came from for Ella Mae’s character. At an early age, I developed a love for reading and writing and began cultivating a dream that one day I could find my name on the New York Time’s Best Seller List. Although my favorite fictional characters growing up were Anne of Green Gables and Josephine March from Little Women, in college I discovered literary fiction and fell in love with Mark Helprin’s A Soldier of the Great War. At that time, I concluded that in order to be successful, I must write in a similar male voice if I wanted to receive credit and acclaim from male critics. It wasn’t until I was an adult that I, like Anne Shirley and Jo March, circled back to the simplicity of my early love for imagination and literature, and it was this mindset which inspired me to write WHERE THIS ROAD ENDS. When I was young, like Ella Mae, I was always in a corner with my nose in a book or lost in my own imagination, creating stories. I wrote my first full length novel when I was fifteen (in the olden days of paper and pen and hardback encyclopedias!) and by the time I graduated high school, it had evolved into a three-book series. I was full of hope, and then… Life happened. As it does to everyone. And I lost faith in myself and in my dream. When I moved to Ridgely, Maryland, I had already self-published two different series, six books total, and I was in a much more hopeful place. I was inspired by the old town charm and the 1895 house which I was living in (it now has a new caretaker). How often do you get to include your own home in an historical fiction novel? I was pretty excited about it! It is known by locals as the John Jarrell House and was constructed as a boarding house during a time of growth in Ridgely, thanks to the fertile farmlands and the railroad. The doors on the house still bore the brass numbers and one of the wooden double doors to the room I used as my office was still stenciled in old time type: “Office.” In the backyard, the barn still stood which had served as a carriage house for the horses and buggies of the family and guests. It was easy to place myself in a different time period and imagine my characters living in the house and walking the streets of Ridgely. Like so many other small Eastern Shore towns, the survival of Ridgely was directly linked to its ability to ship goods through the railroad, so the title of the series seemed like a logical tribute. In typical eccentric writer fashion, I holed myself up from the world throughout the winter months and did little else but research and write in my spare time. I also began planning the cover for the novel, and it only seemed natural for it to include a picture of the old railroad station. It wasn’t until I emerged from my hermitage in the spring that I learned the local historical society had been working to preserve the station and it would be ready for its grand debut at the same time I was ready to call in my graphic designer. Talk about perfect timing! Recently this novel was reviewed as “A sweet, but sad, story.” I promise it has a happy ending! Not every love story does. My daughter refuses to watch Little Women with me since Jo and Teddy don’t end up together. But in the spirit of Anne Shirley finally finding her soulmate in Gilbert, Ella Mae will marry Daniel to satisfy that longing in all our hearts! For personal reasons, this will always be one of my favorites of the novels I’ve written. My hope for readers is that you will not only learn more about the historical time period and old time Ridgely, but be inspired to grow from your trials and suffering and never lose hope! As I work on my next novel series, I thought I would take some time to revisit the RIDGELY RAILS LEGACY. The following is an article printed in the September issue of the Caroline Review Magazine, out of Denton, Maryland. A town so small that it doesn’t have a single traffic light might not seem like a worthy setting for a novel, but as an author with a vivid imagination and a love of history, I found Ridgely, Maryland, perfect for my generational small-town-America series.

I didn’t grow up on the Eastern Shore, but my father did and we often came here to visit family. Some of my earliest memories are of riding in the old station wagon across a great expanse of water on the narrow road which spanned it. I usually had my nose in a book, so my mother would make sure that I didn’t miss it. I would peer out the window at the waves far below as we traveled across the two-lane bridge to the other side of the Chesapeake Bay, where we would enter what seemed like another world. The land was flat and once the water had faded from view, the roads were lined with fields and pastures interspersed with towns that captured my young mind with their Victorian architecture and fading glory. As an adult, I had the opportunity to move into such a town and into just such a house as I had always dreamed. (Little did I imagine I would one day marry a local resident and historian!) It inspired me to learn all I could about Ridgely and to use it as the background for my next series. This was achieved thanks to a gentleman who saw the value of his hometown and captured as much of its history as he could through old newspapers and interviews with senior citizens and compiled them into booklets. Tommy Rampmeyer’s collection was an invaluable resource to me as I researched the town’s history and development through the years. The town of Ridgely didn’t come into being until 1867 when farmland owned by Thomas Bell and the Reverend Greenbury W. Ridgely was purchased by the Maryland and Baltimore Land Association. They mapped out their plans for a grand city which would boast wide boulevards, beautiful parks, prosperous factories and stores, and which would sprawl as far as the Choptank River, with busy docks and a successful shipyard. This “dream city” died, however, when the Land Association went bankrupt within its first year. Ridgely consisted of only four buildings, including a railroad station, hotel, and two private residences. One of these was owned by James K. Saulsbury and was known as the “Ridgely House.” Today, it serves as the Town Hall building. Ridgely would have remained no more than a crossroads on a map if not for the railroad. Lots were sold at public auction, the surrounding area was settled by farmers, and an economy based on crop production was established. Strawberries, peaches, huckleberries, vegetables, eggs, and poultry were shipped out to be sold in larger towns and cities throughout the Eastern Seaboard. The Ridgely train station became a bustling center of business. Many towns on the Eastern Shore which are now rundown or mere stopping points on the way to somewhere else flourished during this age, when commerce depended on riverways and railroads. Thus, as a tribute to its roots—memorialized by the train station museum in the center of town—I named my series “The Ridgely Rails Legacy.” This series chronicles the growth of the town as it follows three generations of women. The first is Ella Mae, a young woman who grew up on a farm just outside of town in the late 1800s. The second book in the series picks up with her daughter Sophie in 1915, when the United States is inching closer to The Great War. The third book concludes with Gloria, Ella Mae’s granddaughter, who experiences World War Two on the homefront. Each woman must face the unique obstacles of her era while holding on to her faith, to family, and to the men they love. A sweeping saga following three generations of women through the most dynamic and rapidly changing times in American history, The Ridgely Rails Legacy series is also rich with local history and bound to be appreciated by both Caroline County residents and fans of historical fiction/romance. Book 1: Where This Road Ends 1895--Ella Mae Hutchins knows exactly what she wants from life. Getting it turns out to be much harder than she expects. She has only two dreams: to marry Daniel Evans and to become a successful novelist. When neither dream seems achievable, she sets out to build a life without either. Book 2: Along the Way 1915--Sophie is a teenager when the United States joins the Great War and mandatory conscription is enacted. All her dreams hang in the balance when her fiancé is drafted and sent to France to fight in the trenches. Book 3: A Passing Mist 1943--After the United States enters World War Two, Gloria joins the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps in hopes of adventure. Her escape is short-lived, however, and duty calls her back to the family farm—but returning to Ridgely means facing memories she’d rather leave behind. As she struggles to make peace with her past, a new challenge arises. German POWs are hired to help work the farm. Gloria never imagined she would find love again, and certainly not with a man on the wrong side of the war. *All my novels are available for purchase in paperback or kindle formats on Amazon. As promised, here is the update on my latest work in progress! I'm so excited to share with you what I'm currently researching and writing. Nothing beats the adrenaline rush of a new project!

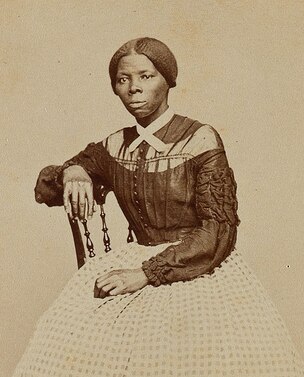

ADRIFT ON WINDS OF CHANGE is book one in the AMERICAN HERITAGE SERIES, which will chronicle three important phases in the history of our nation. Beginning with the Revolutionary War era, then moving into the period of Manifest Destiny and concluding with the War Between the States, I hope to entertain and educate readers with fictional stories rooted in historical settings. On March 10, 1913, the world lost an icon of courage and compassion. Although Harriet Tubman was born into slavery, and was a Black woman in a time when women had few rights and Blacks had none, she possessed a fierce spirit which would not be controlled by anyone or limited by anything! She was only five feet tall, but Harriet was a force to be reckoned with!

When I read the Freedom Train about her rescue missions as a child, I was inspired by her daring as much as by her dedication to helping her friends and family achieve the same glorious sensation of liberty she experienced when she crossed over the line into the free state of Pennsylvania. Harriet Tubman is remembered for having delivered as many as 70 people on her 13 trips into the South, risking her own freedom and safety by returning to the Eastern Shore of Maryland where she had been enslaved and leading groups of men, women, and children north into freedom. When writing THE TIME RETURNS SERIES, which explores local history as well as the roots of racism in the institution of slavery, I felt it appropriate to dedicate a portion of the second novel to my character Natalie Winslow's research of Harriet Tubman. While there are many well known anecdotes which have been share in biographies or movies, I learned much about this incredible woman which is not common knowledge. For example, John Brown, famous for his efforts to incite a slave rebellion in Harpers Ferry, WV., in 1859, had great respect for Harriet and referred to her as "General Tubman"--quite a compliment from the fiery abolitionist who led a raid on a Union Armory and refused to be rescued from jail after his capture, choosing instead to be hung as a martyr for the sake of the cause. Although Harriet Tubman was unable to participate in the raid, she assisted Brown in recruiting men and providing valuable knowledge and support. Several years later, when the War Between the States broke out, Tubman criticized President Lincoln for his lack of decisive action to outlaw slavery even though she joined the Union Army. She hoped that a defeat of the Confederacy would result in the end of the abhorrent practice. In 1863, she was the first woman to plan and lead an armed assault when she guided a regiment of 300 Black soldiers in a raid at Combahee Ferry, S.C., and commanded the gunboats around Confederate mines in the river. The battle was won and resulted in the liberation of 756 people. During the Civil War, Tubman also served as a nurse, caring for soldiers who were wounded or sick. She used her knowledge of herbal medicine to heal them, and was inspired in return by their bravery and strength. In her later years, she opted to have surgery performed on her skull to relieve the pressure caused by a head injury she had sustained as a youth. It had given her severe headaches and dizzy spells throughout her life. Declining the use of anesthesia, Harriet Tubman chose instead to bite down on a bullet as the soldiers had done in the war to cope with the pain of amputation. Talk about tough! Another interesting fact pertains to matrimony. Most people are familiar with Harriet's first husband, John Tubman, from whom she took her last name. (She was born Araminta Ross and changed her first name to Harriet after her escape.) Many are unaware that she married a second time, in 1869, to a Union Veteran named Nelson Charles Davis, who was 22 years younger than she was! (Now that's brave!) They adopted a girl, named Gertie, and lived together as a family in Auburn, New York, until Davis died of tuberculosis in 1888. Additionally it is assumed that she retired from her exciting life of activism after the abolition of slavery. However, Harriet Tubman continued to fight for those who lacked the full benefits of liberty and was an outspoken voice for women's suffrage. She traveled to New York, Boston, and Washington, D.C. to advocate for women's voting rights. In 1897, a newspaper reported a series of receptions to honor her in Boston. It is said she had given so much of her own resources away to those in need that in order to attend, she was forced to sell a cow to afford the train ticket. In 1911, Tubman was frail and her health failing. She was admitted to a rest home named in her honor and was described as "ill and penniless." In 1913, she died of pneumonia, surrounded by family members and close friends. Her last words were, "I go to prepare a place for you." She was buried at Fort Hill Cemetery in Auburn, New York, with semi-military honors. WHEN THE SUN COMES BACK is the title of the second novel in THE TIME RETURNS SERIES and is taken from one of the code phrases used by Harriet Tubman on the Underground Railroad. In this novel, I give tribute to a woman who was selfless in her dedication to both the broader causes of humanity and the individual instances of need she witnessed in her personal life. Her bravery and strength were equaled only by the kindness which compelled her to live in the service of others. On this day, the 108th anniversary of her death, I want to honor a woman who has been an inspiration to generations to fight for those who are oppressed and to give generously to those in need. Throughout her life, Harriet Tubman attributed her courage and the source of her compassion to God. She is an example to all of us us of what Christian servant leadership should look like. I am confident that when Harriet Tubman entered the gates of heaven, she was greeted with the words, "Well done, my good and faithful servant." Although I originally intended to have completed THE TIME RETURNS by November, Black History Month is the perfect occasion to release the third book in a series which examines the roots of racial prejudice in the institution of slavery while also celebrating the achievements of the Civil Rights movement.

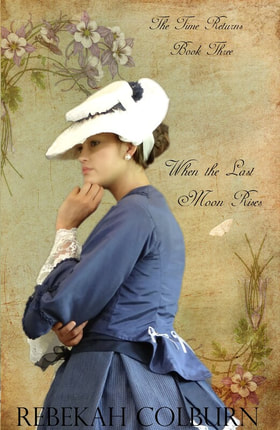

As a writer of historical fiction, I have the unique pleasure of interweaving imaginary characters with real life people and events. My purpose is not only to entertain my readers, but to bring history to life in a way that educates and inspires. Through our study of times gone by, we have the opportunity to gain greater insight into how the present has been shaped by the past. In this series each book has two alternating storylines, one moving forward through the 1960s and 70s, the other moving backwards into the past. The modern story follows Natalie Winslow and Tony Buckle, a Caucasian woman and a Black man on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. It chronicles their controversial romance and marriage, and explores the challenges they face raising mixed children in a place slow to adapt its ideology to the changing times. The historical narrative transports the reader back in time through the brides of the Winslow estate, Dogwood Hall. In the first book, Charity’s diary gives insight into the complications which result when people are divided by skin color and assigned different values instead of being seen as members of the same human race. Her mother-in-law Eliza’s experiences are revealed in book two, as she lives with the consequences of a culture which gives full power to white men and suppresses women and minorities. In this third book, Adelaide’s story develops the foundation of Dogwood Hall in 1798 and the moral dilemma of those who were opposed to slavery and yet benefited from it. Each novel also highlights an historical figure through Natalie’s interest in researching local history. The first book highlights Frederick Douglass, the second gives tribute to Harriet Tubman, and the third focuses on the notorious exploits of Patty Cannon and her gang. Regrettably, the accounts of the kidnapping and sale of fugitive slaves or freed blacks are based on historical records. As the two storylines are laid out next to one another—separated by more than one hundred years—it becomes apparent that great progress has been achieved in promoting racial equality. However, even as we celebrate how far we’ve come, I hope we will be inspired to continue working together to peacefully advocate for the unity of all mankind. Writing WHEN THE LAST MOON RISES in 2021, I am grieved that incidences of racial prejudice and misunderstanding continue to exist. When I began this series two years ago, I could not have anticipated how relevant it would become. My original motive was curiosity to better understand the past, but it has grown into something greater—a call to action to strive for equality, harmony, and genuine Christ-like love. “So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.” Genesis 1:27 NIV

|

Rebekah Colburn Novelist Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed