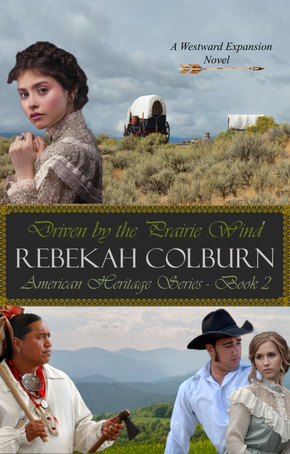

| It may be a while before the third book in the series is completed, but I wanted to share the cover and synopsis with you. If you haven't read books 1 and 2 in the series, you still have plenty of time! Wooed by the Dixie Wind Book 3 of the American Heritage Series: A Civil War Novel 1861 – Bryantown, Charles County, Maryland When anyone could be arrested without cause and jailed without trial, and Federal troops are sent to occupy the county, Rosemary Jameson realizes why her brothers have been so outspoken about fighting for freedom from tyranny. Despite her strong anti-slavery stance, she soon finds herself involved with a ring of Confederate spies. Bobby Bloodsworth was unprepared for the cultural climate when he moved to Southern Maryland. Educated in the north, he brought with him the stereotypes and ideologies he had been taught. As he spends time with Rosemary, he learns that everything isn’t as simple as he had once believed. Despite their political differences, the two find their attraction and affection for one another growing. When he left Philadelphia for Bryantown, Bobby never imagined he would fall in love with his own “Rebel Rose.” Rosemary and her friends never could have anticipated what would happen in the spring of 1865 when a plan to kidnap Abraham Lincoln is foiled and he is instead assassinated. After John Wilkes Boothe makes his escape through their hometown, any connection to the Confederate underground is dangerous and could land them on trial for conspiracy to murder the President of the United States. |

|

0 Comments

If you're always looking for your next book to read, I have great news! My murder mystery is now available on Amazon, and I will be providing information on local book signing events in the near future.

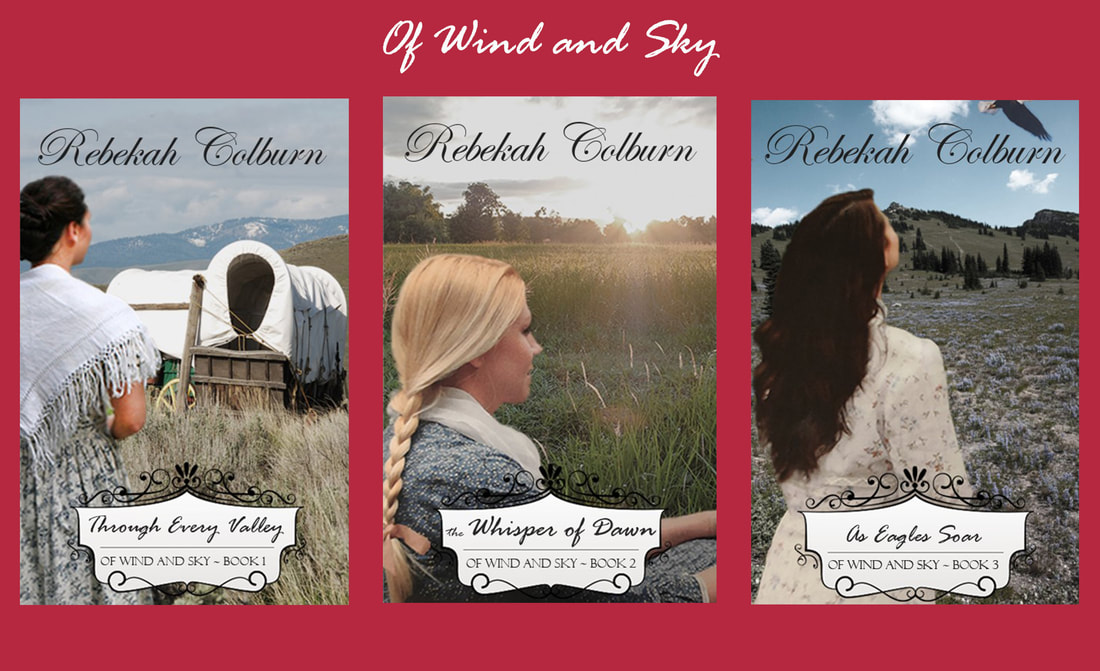

And, if you haven't read the series that launched my career as a historical fiction novelist, OF WIND AND SKY, now is the perfect time! While I was busy on Photoshop creating a cover for my murder mystery, I was inspired to re-release my first series with new covers. Yes, I have ADHD. Haha! But I put it to good use. I also paint furniture and plaques, and I'm still working on researching and writing the next book in the AMERICAN HERITAGE SERIES. As they say, no moss grows under my feet! If you’re familiar with my work, you know this isn’t my usual genre of fiction. Over the winter, while recovering from flu, sinus infection, and bronchitis, I decided to take a little break from serious historical fiction to write a short, fun little project. So, I wrote a murder mystery based on a real-life murder. The original article which sparked my interest was posted by Project Flashback-Centreville’s Facebook Page, and was a special dispatch sent to the Baltimore Sun on August 26, 1911. I was intrigued by the details of a cold case which was never solved. My writer’s mind began asking questions and the next thing I knew, I realized I had the makings of a murder mystery. It will be available on Amazon in March of 2024.

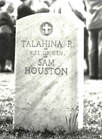

I’m in this picture. If you look closely, very closely—you might need to zoom in—you’ll see that the tiny thing at the base of this statue is actually me. Yes, I’m a small woman; but also yes, the statue is huge. If you know anything about history, especially Texas history, you’ve at least heard of Sam Houston. When I began researching for this novel, I didn’t know a whole lot about him. The more I studied his life, the more I discovered what an interesting and complex person he was. He was relevant to DRIVEN BY THE PRAIRIE WIND because he was the first president of the Republic of Texas, in office at the time that Risdon and Lucy Bloodsworth learn they can have “free land” if they can simply cross the country to stake their claim, live for five years on the property, and make improvements to it. I didn’t take a particular interest in Sam Houston until I discovered that he also had connections to my Cherokee characters, Caleb and Jane Lowe. As I researched back and forth between the details for both storylines, I kept encountering the same man: Sam Houston. I never expected him to be the common thread that weaves back and forth between these two different worlds, but his name kept popping up in Texas and in the Cherokee Nation. Since I found his life story to be noteworthy, I thought I would share some of the highlights, including: his adoption by the Cherokees; the odd circumstances of his resignation as governor of Tennessee after a very brief, failed marriage; and his propensity for violence and drunkenness oddly mixed with moral courage—which may have led to his military and political success. I mean, he beat the Mexican Army in eighteen minutes! All in all, he’s a fascinating character.

Don’t picture them living in teepees! First of all, Cherokee lived in houses built of logs, not structures made with poles and animal skins. Secondly, like so many other Cherokee, John Jolly was mixed-race and lived as a wealthy slave-owning planter, cattle rancher, and merchant. In addition to his fields and orchards, he owned a trading post, successful because of its location on the water. Although Jolly did not speak English, he likely understood it well, in addition to other trade languages such as French.

Houston was shot in the upper thigh with an arrow and not expected to live through the night. He recovered however, and, in May of 1817 was promoted to first lieutenant. The same year, after a treaty was negotiated with the Cherokee to voluntarily resettle in Arkansas Territory, Sam Houston was appointed by President Jackson as a sub-agent to administer the treaty. Believing that relocation was inevitable, and that the Cherokee would live more peaceful lives in the west, Houston accepted. He led a detachment including his adopted father, Chief John Jolly, to their new home in the Midwest. The following year, 1818, Houston received a strong reprimand from Secretary of War John C. Calhoun (whose name is associated with secession and who resigned from his role as Vice President under Jackson to represent South Carolina as a senator). Sam Houston arrived in Native American dress to a meeting with the Cherokee leaders and Calhoun. His intention was to demonstrate respect to the Cherokee, but Secretary of War Calhoun was not impressed. He felt it was unbecoming behavior for an officer and held the faux pas against Houston for the rest of his life.

Eliza told her friend, Balie Peyton, that although she was optimistic going into the marriage, she had sound reasons for not remaining with him. She confessed that he was jealous and often suspicious, even locking her in their room so that she had no food until late at night. He didn’t want her to speak to others even at her aunt's house, where he wanted her to remain in her room when Houston was not around. She told Peyton that she left him because he "evinced no confidence in my integrity and had no respect for my intelligence, or trust in my discretion." Houston seemed clueless as to what had happened in his relationship (typical man?). He wrote to his new father-in-law in April, expressing his confusion over his wife’s seeming indifference toward him and asked for advice on how to restore their relationship. Two days later, when Houston traveled to Cockrill Springs for an election debate, Eliza returned to her family on horseback. When Houston was asked to make an official statement about the separation, he said "I can make no explanation. I exonerate this lady fully, and do not justify myself." On the 15th of April, he went to Eliza and knelt on his knees before her, begging with “dramatic force” to take him back and return to Nashville with him. She was unmoved. The following day Sam Houston resigned as governor of Tennessee. According to reports, on April 23 he wore a disguise and boarded a steamboat out of Nashville. He went to Arkansas Territory and returned to the place where he was most comfortable: with the Cherokee Nation and his adoptive father, John Jolly. En route, however, Houston was intercepted by Eliza’s brothers who explained that there were a number of rumors surrounding his separation from their sister. Houston told the brothers to "go back and publish in the Nashville papers that if any wretch ever dares to utter a word against the purity of Mrs. Houston I will come back and write the libel in his heart's blood." Such an interesting break-up! Once in the home of John Jolly, Sam Houston “Raven” is reputed to have said: "When I lay myself down to sleep that night I felt like a weary wanderer returned at last to his father's house." He fully assimilated into Cherokee culture, adopting their clothing, customs, and language. He was adopted into the tribe and became a citizen of the Cherokee Nation. I wish I could say that at this time he found peace. Although prior to this heartbreak, he may have had a drinking problem, now he earned a new name among the Cherokee people: "Big Drunk." He also lost the approval of Andrew Jackson, who had helped him become a congressman and the governor of Tennessee. (No big loss.)

Now, if you think current politics are nasty, just listen to this story! There was an Ohio Congressman named William Stanbery who was not a fan of Jackson (can’t blame him), and who accused Houston of colluding with the government to defraud the Cherokee while he was Governor of Tennessee. As you can imagine, Sam didn’t respond too well to this accusation. He wanted either an apology or a duel. Stanbery refused to give him either. On April 13, 1832, Sam Houston and two members of the U.S. Senate were walking along Pennsylvania Avenue on their way to the theater. Unfortunately for Stanbery, he chose this exact time to leave Mrs. Queen's boarding house and go for a walk. Mr. Stanbery has been described as “a vile toad of a man” with “black ink drops for eyes that sat too close together on his melon-like head. Long creases on his face emphasized his thin, broad, perpetually downturned mouth.” I’m sure after reading that, you’re as curious as I was to what this man really looked like. So, here he is…

Texas was at that time not a part of the United States, but of Mexico. Nevertheless, the Mexican government had invited Americans to settle on their land. Houston took the opportunity and was able to obtain property in this new frontier. Additionally, President Jackson invited him to negotiate with the Comanche and other Native Americans to try to maintain peace as the government continued to push the Cherokee farther west into territories previously held by other tribes. Houston was always eager to negotiate for the best interest of the Cherokee people and gladly accepted the mission. He settled in the town of Nacogdoches, Texas and opened a law practice. He also pursued a divorce from his first wife, Eliza Allen, (apparently, they had been legally married throughout his relationship with Tiana). The divorce was granted in 1837 and Eliza remarried in 1840. Houston reentered politics, serving as a delegate for Nacogdoches in 1833, proposing to the Mexican Congress that Texas be separated from Coahuila and granted statehood. No such agreement was made, and in 1834, Antonio López de Santa Anna assumed the presidency.

He maneuvered a series of strategic retreats to buy time. In April of 1836, on the banks of the San Jacinto River, the two armies finally clashed. Channeling all their fury from the massacre of the Americans at the Alamo, Houston’s men defeated a force twice its size in just 18 minutes. Sam Houston’s horse, Saracen, was shot beneath him and Houston suffered a severe wound above his ankle. Nevertheless, they had achieved victory and Santa Anna surrendered. An armistice was signed granting Texas independence from Mexico. Houston was a hero, and when elections for president were held in the newly established Republic of Texas, it’s no surprise that he was chosen to lead the new government. During that time, he negotiated for his old friends, the Cherokee, to peacefully live within the borders of the Republic of Texas. His successor, Mirabeau Larimore, had very different ideas about the Native Americans.

In 1841, Houston was elected as the third president of the Republic of Texas. When Texas joined the union in 1845, Houston became one of its two United States senators. He ran for governor in 1857 but was defeated. He ran again in 1859 and was elected Governor of Texas. Although he was a slaveowner, Houston had always voted against the spread of slavery into new territories. He furthermore was a Unionist and opposed to any ideas of sectionalism or secession. Because of this unique Southern position, the National Union party convention in Baltimore almost nominated him as a Presidential candidate in 1860, but he narrowly lost to John Bell.

In the face of national threats, it’s not always clear which course of action is the best way forward. How to mitigate the unavoidable losses and ensure there is a foundation left upon which the nation can rebuild. This was the situation the Cherokee Nation found itself in during the 1830s. President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act into law; its goal was to relocate native tribes from their respective lands (regardless of any prior treaties) and push them onto the newly created “Indian Territory” west of the Mississippi River. This was still a vast frontier, largely undeveloped, and seemed like a good place to put an unwanted people group. Treaties were negotiated with the “Indians” to exchange their ancestral lands for designated tribal territories in the west. The word negotiate is used loosely here. They weren’t given much choice. Even the Five Civilized Tribes, despite efforts to assimilate, were still viewed by their white counterparts as both inferior and as a threat to their own development and resources. In 1830, it was the Choctaw; in 1832, the Chickasaws and Muscogee (also known as Creeks); in 1832 and 33, the Seminole were pushed out of Florida. The Cherokee in North Carolina and Georgia were the last hold-out tribe. They didn’t want to give up. They didn’t want to give in. Well, at least some of them. And that’s where it starts to get interesting. There was no unified opinion as to whether they should stay or go. It wasn’t just “Andrew Jackson v. the Cherokees,” there were different ideas within the Cherokee Nation about what was best for their future, and a lot of inner conflicts within the Nation resulted. These pictures are from the Museum of the Cherokee, in North Carolina. It is titled the “Chamber of Dissenting Voices” and the inscription reads:

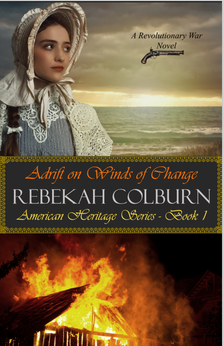

This statue represents three factions of the Cherokees and the different paths they took because of Removal. Oconaluftee Citizen Party These Citizen Indians form the core of the present-day Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians. They had applied to become U.S. citizens, taking advantage of a treaty clause which allowed them to separate from the Cherokee Nation and occupy private reservations and ceded lands. The Treaty Party The Treaty Party was led by Major Ridge, his son, John Ridge, and his nephew, Elias Boudinot. Originally opposed to removal, they came to believe that it was the best policy, and in December 1835, they signed the Treaty of New Echota which ceded their eastern homeland for five million dollars and western land. Looked upon as traitors by the majority of the Cherokee Nation, the Treaty Party leaders, including the Ridges and Boudinot, were later executed for “selling their birthrights.” John Ross and the Cherokee Nation The majority of the Cherokee Nation wanted to stay on their homeland and fought with every legal means available. Some lobbied in Washington, others fought legal battles, such as Worcester v. Georgia. But in the end, all their efforts failed and they were forcibly removed to Indian Territory. Their tragic journey west became known as the “Trail of Tears.” Having read multiple books delving into the motives and specific actions of all three parties, I find this explanation to be an oversimplification. For now, I will only say that the Treaty of New Echota was the means by which Andrew Jackson achieved his goal of removing the final, protesting tribe to Indian Territory. The majority of the Cherokee Nation did not consent to it. It was not approved by either the Council or the Principal Chief. It should never have been regarded as a legal and binding contract. Members of the Treaty Party signed as representatives of the Cherokee Nation, although they were not recognized by it as legitimate delegates. Legally, they were just a rogue faction assuming authority they didn’t possess. President Andrew Jackson knew it. Indian Commissioner John F. Schermerhorn knew it. Federal Indian Agent Ben Currey knew it. They accepted it anyway because it suited their purposes. In my novel, DRIVEN BY THE PRAIRIE WIND, I have tried to bring to life this complicated story and present the different Cherokee factions as they fight for survival in a world that didn’t have room for them. Did you know that the Chesapeake Bay was teeming with pirates during the Revolutionary War? One in particular made the perfect nemesis for the first novel in this series, ADRIFT ON WINDS OF CHANGE.

THE AMERICAN HERITAGE SERIES follows the fictional Bloodsworth family from the 1770s through the 1860s, highlighting the history of the United States through three of its most formative eras. BOOK 1, ADRIFT ON WINDS OF CHANGE documents the founding of our nation through the eyes of Elias Bloodsworth and his wife, Charlotte. They had created their own paradise on Bloodsworth Island in the Chesapeake Bay just prior to the American War of Independence, only to find themselves under attack by the infamous pirate and personal rival of Elias, Joseph Wheland, Jr. During this dangerous time of intrigue, despite accusations of being a traitor, Elias Bloodsworth steps forward as a voice to the public through his letters to the editor, outlining the reasons why they must take the daring step of breaking away from Britain and forging their own nation. This novel chronicles the formation of the Republic, and the chaos, fear, and violence which erupt during this period of uncertainty. Under the flag of the Crown, men like Wheland could privateer without ramifications, legally continuing their ways of piracy and destruction. If you haven’t read Book 1 yet, you can view it on Amazon: Adrift on Winds of Change: Colburn, Rebekah: 9798432175373: Amazon.com: Books Book 2, DRIVEN BY THE PRAIRIE WIND, is told through the eyes of their great-grandchildren. Weaving two storylines together, I wanted to share the broader picture of Westward Expansion and its impact on the developing nation as well as those who originally inhabited the continent. While Risdon and Lucy share the excitement of new opportunities and the perils of the wagon trains, his cousin Jane and her Cherokee husband live the consequences of the ideology of Manifest Destiny as they are removed from their established home and forced to walk the Trail of Tears. In the next book—yes, I am already writing Book 3!—I want to bring to life the more complex stories of the Civil War that have been lost to history. Although we like everything to be neat and simple and to fit into tidy boxes, real life isn't quite that way! In this novel, I wish to share the intricacies of the time period from the perspective of a Southern Maryland family. Watch for BOOK 3, WOOED BY THE DIXIE WIND. Through these fictional novels, I hope to share a new perspective on the history of our nation. I was raised when “Little House on the Prairie” and the 1970’s series “The Oregon Trail” were showing on the TV. I loved Laura Ingalls! Nowadays, little girls dress like princesses; I dressed like a pioneer girl. I read all the Little House books and as I grew older, I remember reading historical romance novels involving wagon trains and wild Indians. One tendency of human nature is to compartmentalize. To forget that while the westward expansion was an exciting time of opportunity for some, it was a time of tragic loss and hardship for others. The overtaking of the continent by European-Americans was only possible because of the defeat of the Native Americans. From our country’s earliest inhabitation by white men, the tribes which had first resided on the land were pushed out. This was to become the legacy of the United States of America. All the native peoples were herded from their homes and confined to designated areas, whether reservations or Indian Territory. As much as I enjoyed Little House on the Prairie, I was also raised with the oral tradition that my maternal grandfather was half-Cherokee. I find the wagon trains exciting: I still wish I could experience the adventure of traveling across the country to conquer the frontier. And yet, I lament that it came at the cost of the people who were here first, who (for the most part) were willing to live peaceably with their invaders. It was my goal in writing this novel to convey both sides of the story. To weave them together in a way that would break down the compartments in the mind and reveal the truth of history. Few events are simple or clearcut once we give them proper study. For my characters Risdon and Lucy Bloodsworth, the offer of free land in Texas is an opportunity to develop a larger farm and legacy than they ever could otherwise on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. They are young and adventurous, full of hope and curiosity. They are eager to take control of their lives and build something new, not just for themselves, but for their country. I can’t blame them. In their place, I might be tempted to do the exact same thing! I never once thought that Pa and Ma Ingalls were threatening or villainous in any way. They were just ordinary folks who were trying to live their lives and provide for their families the best they could. They had no prejudice against Indians. I don’t think it really occurred to them that they were moving into lands previously lived on by Indians, and if it did, they just took it as the way of the times. We are all a product of our time and culture. For them, this was just the way things worked at that time and place. The Indians were being moved west; the land was available to them. It wasn’t until I was a teenager that I became sensitive to the plight of the Indians and the injustice of their removal from ancestral lands. When I learned that I had a family connection with Native Americans, my sympathy for their situation was deepened. But I still love Laura Ingalls and have a desire to explore new frontiers. As in any other historical era, it is the government which makes decisions and the citizens who live with the consequences. There was a prevailing idea among the lawmakers of that day that God had given this land to white Americans. This concept almost became its own religion. The phrase “Manifest Destiny” was first coined on December 27, 1845 by John O’Sullivan, editor of the New York Morning News. Although he was addressing the boundary dispute with Britain over the state of Oregon, the phrase encapsulates a decades old ideology. His argument was that it was “the right of our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of liberty and federated self-government entrusted to us.” Not everyone agreed. A year later, on January 3, 1846, Representative Robert Winthrop ridiculed the concept in Congress, saying, "I suppose the right of a manifest destiny to spread will not be admitted to exist in any nation except the universal Yankee nation." Although he was the first critic of the concept, he was not the last. The argument for “Divine Providence” as justification for actions motivated by bigotry and greed was met with disdain and embarrassment by those who had a more humble and compassionate perspective. Nevertheless, expansionists embraced the phrase and touted the success of their efforts as God’s blessing. In 1996, historian William E. Weeks noted that three key themes were usually expressed by advocates of Manifest Destiny: 1.) the virtue of the American people and their institutions; 2.) the mission to spread these institutions, thereby redeeming and remaking the world in the image of the United States; 3.) the destiny under God to do this work. Long before the term “Manifest Destiny” existed, the principal was alive and motiving such men as President Andrew Jackson when he signed the Indian Removal Act. Now please understand, I am an American patriot, and I would rather live in the United States than any other place in the world. But I am not naïve to the sins of our forefathers. The Trail of Tears was a travesty of justice and a preventable crime. I also love the Ingalls Family. Life is messy. According to oral tradition, my grandfather was half Cherokee. My mother was raised with this belief and recalls her mother watching the old TV series about the Oregon Trail and saying she would have liked to have lived during that era--if it hadn’t been for “the damned Indians and their fire water.” This was a personal jab aimed at my grandfather, who had a drinking problem. His heritage was not important to him, nor was it a matter of interest in the 1950s when my mother was growing up. My grandfather’s family lived in Georgia, and my mom has a vague memory of visiting an aunt there. That’s all I know. My grandmother was of Irish descent, and as you can see in this picture of them together, he looks very swarthy compared to her. In the picture of him wearing his military uniform, you can see his high cheekbones and broad nose, both of which are features of the Cherokee people. I have put many hours into researching my genealogy and trying to unearth some evidence to support the Cherokee story. Unfortunately, I found next to nothing. Although there is a reminiscence written by a relative of migration from a Cherokee area in North Carolina to another primarily Cherokee area in Georgia—with the use of such words as “band,” “clan,” and “traditions”—all of my family members registered as white on the census records.

Were they Cherokee? Was there an intermarriage somewhere that wasn’t recorded? Did they identify as white to avoid mistreatment and relocation? Did they accept citizenship in Georgia to secure their land and safety? Or were they whites who settled on Cherokee lands? These are questions to which I may never know the answer. But the idea of being descended from the Cherokee has influenced me and shaped my interest in Native peoples and their stories. While writing DRIVEN BY THE PRAIRIE WIND, I visited Sequoyah’s cabin in Oklahoma, and it was recommended to me that I join the Cherokee Nation and market my book as “Cherokee Made.” This would have been a dream come true for me, as my interest in and identification with the Cherokee dates back to my early years. However, in order to join the Western Band of Cherokee, I would need to provide the name of an ancestor who was listed on the Dawes Roll and who traveled west to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). My family remained in Georgia, but to join the Eastern Band of Cherokee I would need to provide the name of an ancestor on the Baker Roll from 1924 and meet blood quantum qualifications. Unfortunately, I cannot even find someone who indicated on their census record that they were Cherokee. So, the question remains: am I descended from Cherokee stock? I don’t know why my grandfather would have perpetuated the belief in my grandmother and mother if it didn’t have some basis in fact. Unfortunately, if it is true, it’s a story which has been lost to time. This summer was a very productive season for my writing! The release date for DRIVEN BY THE PRAIRIE WIND is currently set for November 1st, 2023. While my husband (a teacher) was on summer vacation, I had the opportunity to take a road trip with him and explore many of the locations my characters visit in this novel and to perform comprehensive on-site research. This has been, to date, the most challenging novel I’ve ever written! So many periods in history are more complicated than we realize until we start digging deeper into the details. I am excited to share some of the places I visited in future blogs, but today I wanted to reveal my new book cover and synopsis! Watch for more information to come on the brave pioneers who helped to settle America, as well as the Native Americans who were forcefully relocated from their homelands to Indian Territory.

|

Rebekah Colburn Novelist Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed