His oldest son, Charles, had felt compelled to join the Union Army and did so against his father’s wishes. He informed his father in a letter dated March 14, 1863, “I have tried hard to resist the temptation of going without your leave but I cannot any longer," he wrote. "I feel it to be my first duty to do what I can for my country and I would willingly lay down my life for it if it would be of any good.” Charles was severely wounded in the Battle of New Hope Church, a bullet passing under his shoulder blades and damaging his spine.

Henry’s wife, Fanny, whom he had married in 1843, had died tragically in a fire in 1861. She had trimmed her seven year old daughter’s hair, and wanting to keep Edith’s beautiful curls, had prepared to preserve the locks in sealing wax. The day was hot, however, and a breeze blew in through the open window igniting droplets of wax which had fallen unnoticed onto the light material of Fanny’s dress. Almost immediately, she was engulfed in flames.

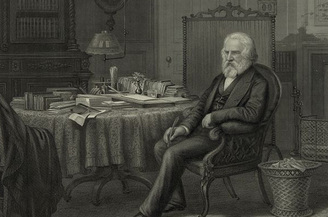

Henry had made every effort to extinguish the flames and save his wife, but the only means at his fingertips was an undersized throw rug on his study floor. When it failed to smother the fire, he threw himself over her, severely burning his face, arms, and hands. The following morning, Fanny Longfellow died. Henry was unable to attend her funeral, both from his burns and from crippling grief.

Frances Appleton was the great love of Longfellow’s life. Their courtship lasted seven years. She was the subject of the sonnet, "The Evening Star," which he wrote in October, 1845.

The first Christmas after Fanny's death, Longfellow wrote, "How inexpressibly sad are all holidays." A year after the incident, he wrote, "I can make no record of these days. Better leave them wrapped in silence. Perhaps someday God will give me peace." Longfellow's journal entry for December 25th 1862 reads: "'A merry Christmas' say the children, but that is no more for me."

Almost a year later, Longfellow received word that his oldest son Charles, a lieutenant in the Army of the Potomac, had been severely wounded. The Christmas of 1863 was silent in Longfellow's journal.

Finally, on Christmas Day of 1864, he wrote the words of the poem, "Christmas Bells." The reelection of Abraham Lincoln or the possible end of the terrible war may have been the occasion for the poem. Lt. Charles Longfellow did not die that Christmas, but lived.

This poem gave birth to the carol, "I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day," and the remaining five stanzas were slightly rearranged in 1872 by John Baptiste Calkin (1827-1905), who also gave us the memorable tune.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed